Having recently watched the new Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, my mind is highly attuned to the realities of being a young person in a rapidly changing world. I left the movie deep in thought, thinking back at how I felt when I was first introduced to “The Times They Are A-Changin” when I was exactly the same age as my students at Compass Montessori Jr. High. Not unlike the early 1960s, the world today, and thus teenagers today, are experiencing massive cultural and technological transformations.

It is easy to forget that adolescents experience these changes very differently from adults as they are biochemically hardwired to blaze their own trails, question the status quo, and create their own culture that distinguishes them from the adults in their life (especially their parents). Moreover, adolescents’ brains experience a neuroplasticity that allows them to adapt to change much better than the fully formed adult brain. Add to this the as-yet-to-be fully understood impacts of fast-paced, high stimulus, globally integrated technologies, and you have the perfect combination for a profoundly different iteration of Homo sapiens. In short, adolescents today are as, if not more different from their parents and grandparents as Bob Dylan was from his.

In watching A Complete Unknown, I was not-so-subtly reminded that my job as an adult, and especially as a Montessori guide, is to “lend a hand” to these next generations and do my best to understand, not judge, and even better, to be curious about the way they experience the world. Dr. Montessori reminds us to “follow the child,” as they are, not as we might hope for them to be. With this in mind, we must remember that the adolescents that we once were, were essential to the adults we are today.

Having said all this, it remains essential to support adolescents in navigating new technologies, and to provide the boundaries young people have, and will always need in order to safely explore the parameters of their personal identities, as well as their aspirations for the future. At Compass Jr. High we do this by providing as many opportunities as we can muster for self-exploration and expression, while also pushing our students outside (sometimes well outside) their comfort zones. Our most powerful tool in this effort is building community, and engaging with a diversity of other communities here in Michigan, and well beyond the borders of our State. And while modern adolescents may, indeed have much to teach us about the future that they will create, we too have much to teach them about how to be a good citizen of that future, even if we ourselves may not quite understand it… yet.

If you’re the parent of an emerging adolescent, you don’t need to be reminded that they are experiencing the first waves of a fundamental shift. They are Montessori’s “social newborn”, working out who and how to be in the society they have inherited. Their brain is undergoing a flood of changes, all of which influence decision making.

You know your kid needs steady adult guidance to help them navigate the increasing complexity of their life. And yet, with the competing interests of friends, activities, and technology, plus a side of attitude, you may be struggling to find a way in.

Does your teen barely acknowledge your bids for connection until 11pm, and then have you hanging on the doorframe while they unspool the day’s drama? Psychologist Lisa Damour encourages us to leave the dishes for the morning and give them our full attention.

Damour’s book, The Emotional Lives of Teenagers, aims to help parents “stay connected to your teen and provide the kind of relationship they need and want”. This means being willing to meet them, sometimes, on their terms.

What Damour hears most often from her clients is the wish that their parents would listen to what they have to say. Really listening, without jumping to solutions or rushing to console, can feel counter to the instinct to protect your child. She writes that “the act of putting feelings into words [may] provide all the relief that’s needed”. When they come to you, ask what they need: do you want help, or do you want to be heard?

It is likely that often, they just want to vent. The better we get at articulating our feelings, the more clarity we feel after talking through them. Help your teen build their emotional vocabulary by drilling down - you’re “mad”; are you also irritated, apprehensive, disgusted, floundering? Supporting them to communicate through, and about, their emotions will increase their self-awareness and build a muscle that supports everyone in the home - empathy.

Giving their emotions our attention helps teens take their feelings seriously. Damour observes that adolescents doubt the validity of their emotions when they compare to how their peers seem to feel. A friend’s snippy comment at lunch really rubbed them the wrong way, but nobody else seemed upset, so they’re probably making a big deal out of nothing. Encourage them to trust their gut and talk together about how they could respond if they choose to.

Feelings are just one piece of data. Encourage them to tap into other ways of knowing, including logic and values, when making decisions. Take the initiative to bring up tricky situations they’re likely to encounter, and help them create a plan that aligns with their goals for themselves.

Often the solutions adolescents come up with are different from what we would have chosen for them. By empathizing, instead of rushing in, we are showing them that they can trust themselves. This is another step toward the independence they’ve been building since they started washing their own dish in the Young Children’s Community.

You may feel frustrated when your teen shows the ability to reason one minute, and makes a regrettable decision the next. They are likely to be frustrated and confused, too! This is part of the journey. All of the work you have done to build trust will help them feel safe to open up in those vulnerable moments.

This blog was inspired by Lisa Damour’s The Emotional Lives of Teenagers. Upper Elementary and Compass Junior High parents are invited to join us for a discussion at Compass on January 28th at 6:30pm.

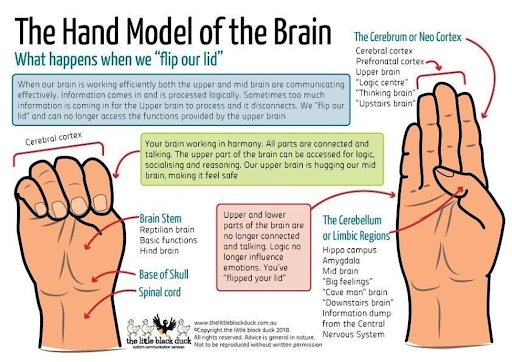

Can you think of a time when your child was in a full-blown state of dysregulation? Have you ever found yourself trying to reason with them in that moment and then become frazzled yourself because they are not open to hearing you? Research today tells us that when any human is experiencing this level of heightened emotion, parts of the brain responsible for reasoning become inaccessible. This is beautifully explained with the “flipped lid” model.

How do we help our children learn skills necessary to cope? Dr. Montessori knew the importance of a neutral state of mind. It is through “Grace and Courtesy” lessons that an adult models certain desired/appropriate behaviors/movement. She understood the importance of allowing children opportunities to practice these skills before they need them. Practicing effective coping skills is a great way to prepare children for those big emotions.

Another tool that has proven to be incredibly effective for children is something called “social stories.” Social stories are books originally created by Carol Gray to help children experiencing Autism cope and find success with the world around them. We now know that these stories can benefit and support all children. They are visual and verbal reminders from the child's perspective of what to do or what to expect when specific situations arise.

A favorite social story of ours talks about anger. The social story:

- Gives language for the emotions such as: being mad, angry or frustrated

- Validates those feelings without shame

- Lists all the ways the child might express their anger

- Sets boundaries on appropriate responses to feeling angry (not hurting others)

- Gives ideas of how to cope

- Naming the emotion

- Talk to a friend or family member

- Ask an adult for help

- Taking deep breaths

- Listen to music, go for a walk, get a sip of water, etc.

- Statement that this feeling won’t last forever, and they can help it pass by quicker if they use a coping strategy

Other situations that social stories can be helpful for:

- Upcoming transitions

- Sleep

- Toileting

- Waiting my turn

- Hitting and pushing

- Change of routines

- Respecting other’s personal space

- Voice volume control

- Greeting others

- And so many more!

These books are meant to be read, not in the moment but rather routinely throughout their day during neutral moments. If you find yourself stuck on how to support your child through a challenging season, consider using the power of a social story. Here are few great resources if you would like to learn more:

https://www.andnextcomesl.com/p/printable-social-stories.html

Compass Montessori Junior High -

On Tuesday, October 22nd our class took our annual trip to Detroit. We stayed in Hostel Detroit for the week. The first day consisted of visiting The Detroit Institute of Arts and getting groceries at Meijer. The Detroit Institute of Arts came with many cool experiences. We split into van groups to tour the museum with our guides. One exhibit we got to enjoy was the Ofrenda exhibit. The beautiful altars pay tribute to loved ones who have passed away. Currently, we are learning about the Day of the Dead in Spanish.

On day two, we headed to the Zekelman Holocaust Center. We learned about the tragic history of the Holocaust. We heard from Holocaust survivors about their heart-wrenching stories and experiences. We also got the chance to view Anne Frank's tree. During World War II Anne Frank went into hiding and she wrote in her journal about this special tree that stood outside her window. This horse chestnut tree gave Anne Frank hope about the future. Scientists found this very tree and created saplings. The saplings were given to many museums around the country. The Zekelman Center was given one and we got an incredible view of this tree. After this museum, we explored the Children’s Science Museum. We explored all the different levels of this amazing museum. We got the opportunity to view a dinosaur exhibit. This exhibit showed us what dinosaurs looked like many years ago as well as interactive displays. During the museum, we watched a documentary on the life of whales. To wrap up day two, Jessica Sullivan kindly got us tickets for the Pistons basketball game. The Detroit Pistons played the Indiana Pacers. The Pistons sadly fell to the Pacers 115 to 109. But it sure was a great game! We enjoyed pizza and got to shoot free throws after the game ended. Our class was also featured on the Jumbotron. This was definitely the highlight of the night for most people.

On day three, we got to catch up on sleep with a late start to our day. Our first activity was at 11:00 when we drove to Historic Fort Wayne. Historic Fort Wayne was a five point star fort where the army would fire their weapons at the Canadian shore. It is also a sacred Native American burial ground which was very sad to see. After the tour we enjoyed a packed lunch and some recess. Once we had finished at the park we decided to walk around downtown Detroit. It was so fun to see all the buildings and sights. Before dinner, we made one last stop which was an old building and we learned all about the architecture. Dinner was at Detroit Shipping Co. It was so good and we had so much fun. We played bags, Connect 4, and of course we couldn't leave without getting the whole class to sing karaoke on two microphones. That was definitely an experience none of us will forget. Before the night ended we went to this pop-up shop called the Pink Flamingo where we bought treats like lemonade and cookies. This night and the game were definitely unforgettable.

On day four, (our last day in Detroit) we woke up very early to pack up. After spending the whole morning packing suitcases, washing sheets and checking everything we headed home. Before fully leaving we made one last stop to the state capital in Lansing. We heard from Betsy Coffia’s legislative director, Ashley. We heard all about how she got into politics and her life. After we heard from her we got a tour of the state capitol. It was very cool. We even got to see Governor Whitmer's office! After the tour, we drove the three hours back to Traverse City.

We would like to thank our guides and chaperones for the opportunity to take this amazing trip. We would also like to thank all of the tour guides that showed us the ropes during many of the museums! Thank you!

Written by Gwennie Goodreau and Ava Hagerty

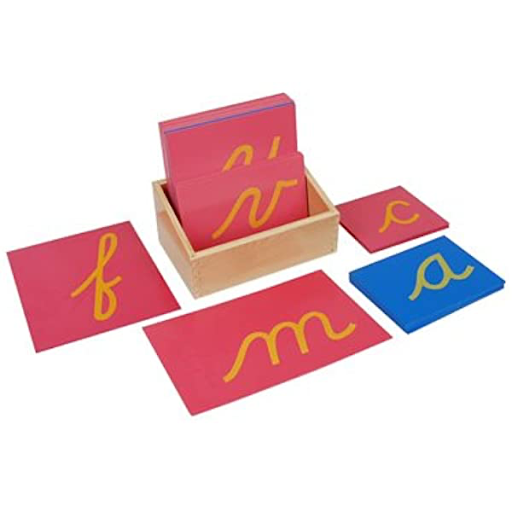

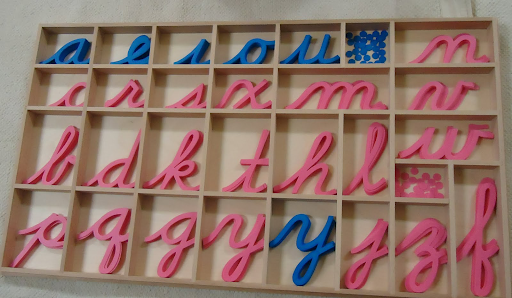

If you were able to join us this past week for our Primary Deep Dive, you heard Alison Breithaupt mention the trio of elements that allow the Montessori ‘magic’ to flow in a classroom. Those essential elements are:

- the training of the guide

- the prepared environment

- and the materials in the classroom.

The materials cannot be used in isolation outside of the context of the other two elements … it simply will not produce the same effect. The topic of this blog is about ‘doing’ Montessori at home and it seems an impossible feat we set before you if all of a sudden the materials – the legacy of Dr. Montessori herself – are now off limits. What if I shared that another harmonious trilogy can be created within the context of your family? It may not produce the same magical melody as we sing in the classroom, but it is a tune of a different nature – and one just as powerful.

You are your child’s very first teacher – their most important guide in life. Schools often lay claim to building a child’s foundation in life. The work we do in the classroom certainly strengthens their base of knowledge, but it is by watching you that your child builds the pillars upon which their foundation rests. You model the values in life that are most worthy to prioritize.

This is a good time to do a quick self-reflection and ensure the habits you are modeling are the ones you want your children to mirror their life after. Is competition for attention at your house fiercely divided among work, household chores or responsibilities, technology, or hobbies? Is your child learning what a healthy work/life balance ratio is? Are they encouraged to make meaningful family contributions in a way that helps them feel valued and worthy? Are spaces in your home designed for your child to create independent routines? Are hooks low enough to hang backpacks and coats, clothes and utensils in accessible drawers, and healthy snacks within reach without support? These minor adjustments can have a resounding effect on your family's rhythms. Is your child learning to have a wholesome relationship with technology – one that teaches them how it can be used as a purposeful tool for progress? Is your family building a collection of hobbies together – ones that will create lasting connections and joint memories?

After looking at the values you model through your actions, the second element to consider is the words we speak. This directly correlates to the message above because sometimes the words our children hear come in through their ears, and other messages they feel directly pierce their heart. If you are familiar with Don Miguel Ruiz’s book, The Four Agreements, you will remember his first agreement, from which all other agreements stem, is to be “impeccable with our words.” This simple act of striving for impeccability will create a channel from which positive energy can flow freely. Just as the bell work in our classroom trains your child’s ear to hear Perfect Pitch, let your words train your child’s ears to listen for truth, wisdom, and love.

The final element needed to round out the trio of our good works and our words is that of presence. Know that every day you show up for your child is enough. The love we have runs so deep that just being there to share the laughs and catch their tears is enough. Teach them how to hold space in their heart for one another when you have to be apart and make the time you have with one another a gift simply by being present.

Authentic experiences come directly from the heart. They speak intentions and truths to your child in a way that no other lesson can. Incorporating Montessori’s philosophy into your home doesn’t have to involve doing anything other than checking the intention behind what you are already doing.

If you look to social media for ideas about Montessori for very young children, you will likely see lots of stuff. There are several materials in our classrooms that would be excellent in a home as well, but I would argue the best way to do Montessori at home is to include your child in as many aspects of daily life as you can. These activities are referred to as the practical life curriculum in our classrooms.

Practical life encompasses all of the activities and actions that we do every day to take care of ourselves, others, and the space that we live in. Some of these activities are related to our basic survival, such as preparing and eating food, and many of them are what we would think of as chores to be done to keep our households running smoothly.

We talk a lot about practical life in the Montessori environment because those exercises encourage so many aspects of development in the young child. Practical life fosters growth in fine motor, gross motor, language, and social-emotional literacy. It also highlights one of the most important skills for a young child to develop: independence.

The most important aspect of doing practical life activities with babies and young toddlers is to have the house prepared for them. This does not mean they need to have a beautiful IKEA kitchen like you may have seen on Instagram. Having a basket of towels that they can access and a place for the wet/dirty ones to go is enough. Smaller utensils are great, but it is more important to allow them to be involved when you feel comfortable doing so than wait until you have all the perfect items.

We do these practical life activities every day in our own homes without thinking about it. Children start their lives with these activities being done to or around them. The child absorbs who does those activities and how that person does them. As children get closer to pulling to stand and walking, they become intensely interested in participating in these activities.

Even the youngest babies watch and absorb everything around them. We can include babies who aren’t able to sit up yet by doing appropriate activities next to them and narrating the process. They are frequently happy to observe us as we move about cleaning our homes and are that much more likely to participate where they can as they are physically able.

Here is a non-exhaustive chart of activities that you might be able to incorporate into your home routines with your children:

| 6-12 months | 12-24 months | 24-36 months | |

| Cleaning the table | -Wiping spills while seated in their high chair | -Retrieving cloth and placing soiled cloth in the laundry basket | -Clearing plates to the sink |

| Laundry | -Load individual items into a front-loading washing machine |

-Loading the washing machine -Flipping laundry to the dryer

|

-Sorting -Folding -Putting their clothes away -Hanging clothes on hangers

|

| Cooking, baking, and meal times |

-Pouring water into cup -Transferring items from cutting board to bowl -Self-feeding -Washing vegetables in a bowl of water

|

-Slicing -Spreading -Adding ingredients -Stirring -Peeling oranges -Shucking corn -Sprinkling (seeds, herbs, etc.) -Using a fork -Setting the table

|

-More advanced knife skills -Scooping -Measuring -Filling muffin tins -Grinding pepper -Peeling vegetables

|

| Care of Home |

-Unloading dishwasher -Water outdoor plants

|

-Loading dishwasher -Watering plants -Dusting shelves -Sweeping -Vacuuming -Mopping -Arranged flowers in vases -Restoring order with help

|

-Sweeping into a dustpan -Cleaning windows and mirrors with vinegar spray -Dusting plant leaves -Cut flower stems -Repotting plants -Restoring order independently

|

| Care of Self |

-Participating in dressing and undressing -Giving two choices for clothing options for the day

|

-Brushing teeth -Brushing hair -Washing hands -Pulling zipper up -Closing velcro on shoes -Independent dressing and undressing -Wiping their nose

|

-Cleaning shoes -Buttoning clothes -Threading zippers -Independently changing shoes

|

Our class traveled to Harbor Springs to learn about the Anishinaabe and their incredible and inspiring history. Eric Hemenway was kind enough to teach us about his culture and the history of Holy Childhood, a Native American boarding school. We stayed at Wilderness State Park for the night and enjoyed Odawa classics that consist of wild rice, squash, and for a main, delicious fish.

When we arrived at the campground, Eric met us and we discussed the history, culture, and traditions of the Anishinaabe. The campground we stayed at was once called Little Fox. While we stayed there, some of the class saw a little fox run across the beach. It was pretty incredible. After dinner, we finished the night off with a closing circle and the option to go to the beach and enjoy the stars. The stars that night were so enlightening.

Day two had many adventures. First, we got up early and enjoyed cornmeal pancakes with blueberry preserves and freshly made eggs. After, we headed to the sight of where Holy Childhood used to stand. Holy Childhood is one of 400 Native American boarding schools. Holy Childhood's goal was to strip Native Americans of their language, culture, traditions, and their family. Many of the survivors expressed how cruel and humiliating the conditions were. After learning about Holy Childhood we drove to Charlevoix and went to an Anishinaabe church and learned more about the tribes. After exploring, we headed home to Traverse City.

We would like to thank our school and teachers for taking us to Harbor Springs to learn about the Anishinaabe. Also, a big thank you to Eric Hemenway for taking time to teach us about his incredible culture.

In the second week of school, our class took a trip to the Michigan Upper Peninsula. First, we visited Fort Michilimackinac. Fort Michilimackinac is a military outpost located in Mackinaw City. After, we visited the famous Soo Locks Boat tour. The Soo locks use gravity to move water in and out of lock chambers, allowing boats to travel through the Great Lakes. For dinner, we ate at this incredible place called “The Wicked Sister”. To wrap up the first day we camped at Tahquamenon Falls. Tahquamenon Falls has over 50,000 gallons of water and has over 500,000 visitors a year.

Day two had many amazing adventures. First, we took a boat to sightsee the beautiful Pictured Rocks. Pictured Rocks was established on October 15, 1966, and is known for its beautiful sandstone cliffs. For lunch, we enjoyed the local delicacy, pasties. After, we drove to our campsite, Baraga State Park. To finish the day off, we enjoyed pizza and hung out at a park.

Day three, we went to a key spot for the economy in 1845 through 1887, The Quincey Copper Mine. We went underground and explored the life of a miner as well as their critical working conditions. For 8th-grade student Henry Davis, we enjoyed ice cream at the Copper Scoop for his birthday. After our delicious treat, we went to a museum about the mining community in the Upper Peninsula. After that, we drove up to an incredible lookout on Brockway Mountain. We enjoyed the golden hour on the mountain. Then we headed to our campsite, Wilkins State Park Where we settled in for the night.

Day four, to start our day off we woke up really early and went to Horseshoe Bay to watch the sunrise. It was so beautiful. After the sunrise, we started the three-hour drive to Cliffs Iron Mine where we learned all about the mine and things that happened in it. We learned a lot of different stories, like one day when the minors were working in one of the shafts it started flooding and three men tried escaping by climbing a ladder. Two of them got sucked into the water but the third made it out. It was a really sad event that killed multiple people. After we learned about the mines, we got into the vans to eat dinner and go to our new campsite, Indian Lake Campground. Since it was the last night we got to do a campfire and smores.

Day five, when we woke up we got in the vans and headed to Kitch-iti-kipi. It is a very beautiful spring and we got on a floating dock that traveled across the springs so we could get a good view. After we finished looking at the gorgeous springs we got in the van and started the long drive back to Traverse City.

We would like to thank our school and teachers for taking us on this incredible trip with many memories and experiences we will never forget. We are forever grateful that we got the opportunity to experience the beauty of the Michigan Upper Peninsula. Thank you!

Written by: Ava and Gwennie, Compass Junior High Biographers

Photo credit: Olivia, Compass Junior High Photographer

Every year the intention of September is to orient new members to our community, challenge our returning 8th years with increased responsibility, and then unite the two groups into one. Week one begins with a staggered start with the 8th years arriving first to discuss their vision for classroom roles and responsibilities. We talk about what it means to be a leader, a mentor, and a role model. They prepare an orientation and a “job fair” of sorts focused on care of the environment as well as the leadership roles such as trip planning, photo, yearbook, and conflict resolution to name a few. Seventh year students then choose their “top three” interests, are interviewed, and ultimately offered apprenticeships.

Our first full day together is focused on creating agreements for living and working together over the course of the year. How do we want to feel? What do we need to learn? How will we work through conflict when it arises? These agreements set the foundation of the conflict resolution process, helping discussions turn us toward the promises that our “best selves” aspire to. Thursday and Friday of the first week, we introduce classroom routines, expectations, and general logistics, as well as an overview of the “NoMi Experience.”

The NoMi Experience is the name given to our week-long excursion that takes place the second week of school; this year our Northern Michigan Experience was a visit to the Upper Peninsula. Why do we travel together for a week to start off the school year? Travel provides challenge, challenge provides opportunities to support one another, as well as reveal our “not so supportive” tendencies. What happens when you’re grumpy? Tired? In need of space? How do you handle it? How do you set boundaries? How do you respect each other’s boundaries? Throughout the trip moments arise that require working together to find solutions that align to our classroom agreements. These discussions also inform changes, or refinements necessary to better understand what our classroom agreements mean and what they look and sound like in practice.

NoMi Highlight Reel

We live in a beautiful place. Michigan’s motto is, “If you seek a pleasant peninsula, look around you.” Our state is made up of two pleasant peninsulas, and we had the opportunity to hit the highlights in the Upper Peninsula.

- Fort Michilimackinac, (the better of the two)

- Soo Locks boat tour where we wave to Canada

- Tahquamenon Falls and the river mouth

- Munising, Muldoon's Pasties (eat like a Yooper)

- Pictured Rocks Boat tour; an overview for the end of the year hike

- Chutes and Ladders in Houghton (the craziest play area I’ve ever seen)

- Quincy Mine, Copper mining near Calumet

- 4Suns- Fish and chips!

- Prospector’s Paradise Rock shop; you want it, they got it!

- Cliff’s Shaft Iron mining; the story of iron mining in the U.P.

- Kitch-iti-kipi; DIY rafting over a natural spring

- Singing on the way home, playing at the rest stops, and sharing meals

In summary, history, engineering, geology, economy, water, culture, immigration, natural resources, stories, food, and fun. And, we had lovely weather to boot.

All of these places play a role in our curriculum over the course of the two year cycle. From industry to stewardship, from first peoples to Democratic movements, and everything in between.

As we wrap up the third week and head into the fourth, systems are starting to settle into place. Our first workshop, FreshWater Ecology, is underway. Tuesday and Thursday we spent at the Timbers learning about the diverse water systems on the property, as well as starting a writing piece based on observations.

This year we have a new opportunity to connect to the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians. Monday we will be on our way north to meet with Eric Hemenway, a tribe historian. We will be eating traditional foods, hearing about the Odawa connection to water, and learning about resilience through the story of the Holy Childhood Boarding School.

As humans, storytelling is how we share information, memories, and lessons. It is also how we connect to each other. Throughout human history stories have helped us progress, from knowing which berries to eat, to knowing when to plant or harvest. Stories also help us find common ground, and unite our efforts to imagine and create new things, as challenges arise. In our travels and conversations with the many people we meet along the way, we get to hear so many stories from the past and present, as well as stories of hopes and dreams of the future. In the few weeks we’ve had so far this year, we’ve heard stories about generations of mining in families, immigration, preservation, shipping on the Great Lakes, peace, conflict, Indigenous people, and so much more. These stories connect us to the past, bring us into the present, and help us write our future.

One of the wonderful things about sending your children to school is that they get to experience a whole world outside of their lives at home. They are experiencing what it’s like to be a part of their school’s community, make friends, connect with the adults, and change and grow as individuals. As parents, we understand the importance of our children having these experiences on their own, but we also want to know about what goes on during their time away from us.

Some parents struggle to get a response from their children when they ask questions like, “How was your day?” It's helpful to have a guide on how to engage with your children so that they feel comfortable opening up and sharing the good (and not-so-good) details about their day at school.

Picking the right moment: Consider your child’s mood and if it is a good time to ask your questions. Give them time to relax. Try not to bombard your child with questions right away after school. Start by just saying, “I am so happy to see you!”

Lower your expectations: Remember that the school day is long and your child is in close quarters with many individuals throughout the day. This can be challenging and exhausting to navigate these relationships and interactions with others.

Celebrating accomplishments: Asking your child when they felt proud of themselves in the day allows your child to focus on their accomplishments and not to focus solely on pleasing others. This fosters a strong sense of self-esteem, intrinsic motivation, and resilience, allowing them to develop a healthy identity based on their achievements rather than external validation.

Hold off on friendship questions: As parents we want our children to feel included and have friends. However, sometimes questions like “Who did you play with today?” or “Who are your friends?” can put pressure on your child that this is important to you and it may not be important to your child or might not be a developmentally appropriate question for their age. Developmentally, children before the age of four, do not feel the need for “friends.” They may prefer to work or play independently. As we all know, social interaction is a basic human need. It is as important as food, water, and shelter when it comes to laying the foundation for the ability to thrive and survive. Rest assured, these needs are being met throughout your child’s day. Friendships may not be a crucial part of this right now. Also, neuro-divergent children may not presently have the skills to develop these relationships. As parents, it is important to meet our children where they are. Unless they voice these needs or concerns around friendships, try to refrain from asking these direct questions.

Many of the questions below may spark this desire for your child to share their social interactions with others.

Ask open-ended questions: Avoid questions that can be answered with a “yes" or “no.” Instead, ask questions that invite more than a one-word answer. Here are some examples of questions you could ask:

“What was the best part of your day?”

“What made you laugh today?”

“What made you happy today?”

“Did anything feel hard today?”

“Did anybody have a hard time today?”

“What was something new you tried today?”

“Did you have any challenges or tough moments today?”

“Did your teacher say anything funny today?”

“What are you looking forward to at school tomorrow?”

Check Your Teacher’s Classroom Highlights: Your child’s guide will be sending you monthly updates on the activities in their classroom. This is a great way to be informed about the classroom and gives you questions to ask your child about school. Please, look for them in your email and on the Classroom Pages.

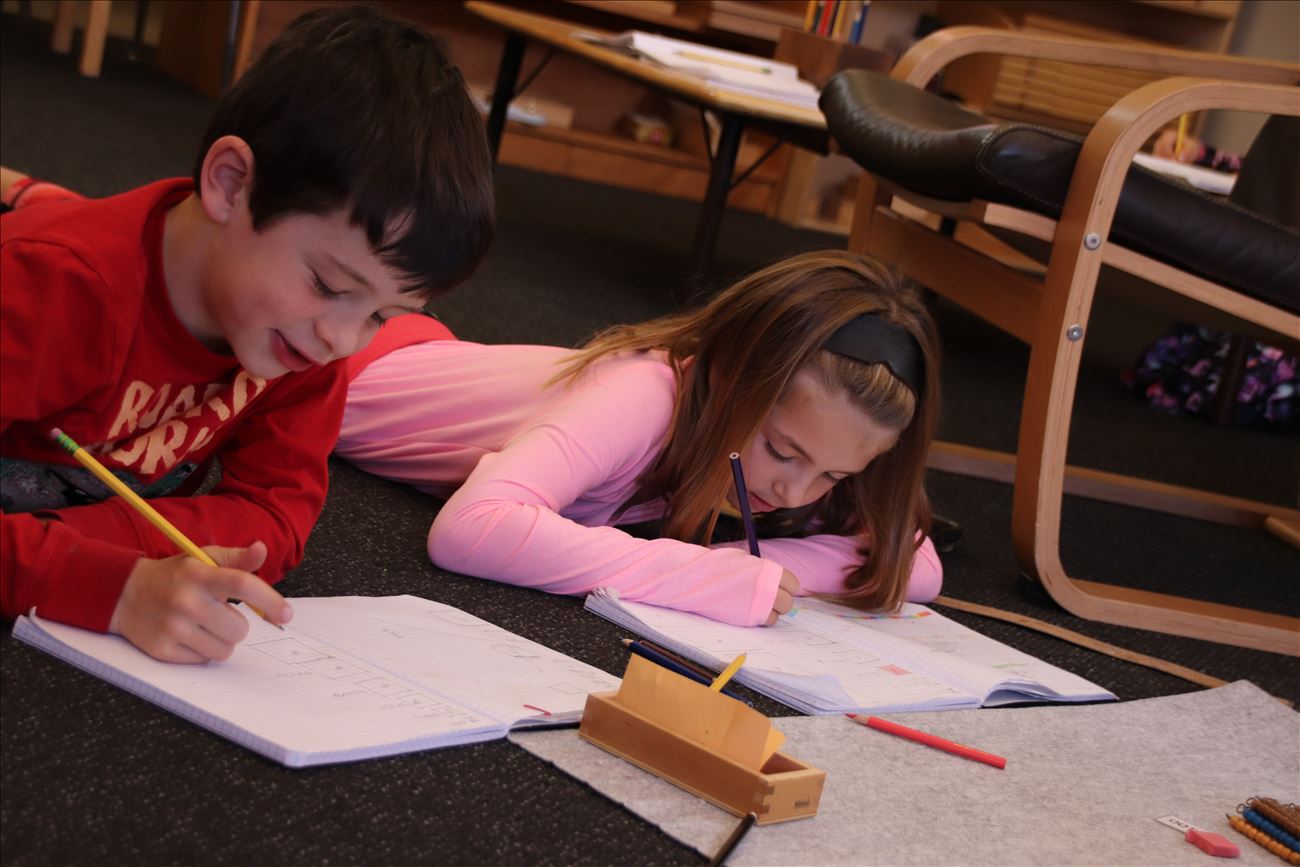

As I sat in a Lower Elementary classroom observing during the morning work cycle, three children surrounded a rug working on a math material.

“It is my turn to move the beads on the bead frame,” one student says.

“No you went last time, it’s my turn,” says another.

The conversation continues and things escalate a bit, with both students believing their perspective is right. One of the adults comes over when she observes the students struggling and acts as a mediator in support of them resolving their conflict. She doesn't offer them the solution, just helps them take turns in the conversation hearing one another’s perspectives. The students come to an agreement and continue the computation.

The Montessori classroom, known as the Prepared Environment, is thoughtfully created to not only support students in their independent learning of academic subjects but also to learn from the earliest stages what it means to work and live in a community. Opportunities for conflict resolution, understanding the perspective and needs of others, friendships, self-care, and mentors and mentees are all an integral part of their daily life at school – even in the Nido.

As the children mature, they begin to learn the language of feelings and emotions and can express them to others in the moment. There is time to pause when situations arise to work through conflicts in real time. Learning about oneself and others occurs organically throughout the day with adult support when needed. Because of this, children learn what it takes to be in relationships with others in a very authentic way, rather than social and emotional learning as a stand-alone curricular element.

Step into any Montessori classroom and observe. Undoubtedly, you will see countless exchanges where social learning is taking place. Not because it is being explicitly taught, but because it is being experienced and supported.

Read more about how our school supports social and emotional learning on this new page in our Family Portal.

Every step of my journey to becoming a guide has felt fortuitous, and I attribute much of this to the unwavering support of my colleagues, family, and friends. Their efforts, going above and beyond, have made my training and my first year in the classroom a genuinely enriching experience.

I began my work here as a substitute across every age group, which solidified for me that elementary was where my heart belonged. I served in an assistant role for two years while going through training, which offered incredible insight into my future practice. I entered my new classroom community with an experienced assistant who provided support, graciousness, and a sense of adventure. I inherited a group of positive parents who have made serving their children daily a joy. Finally, I entered a classroom filled with eager, smiling, giggly, happy, fun students who made every moment (even the hard ones) worth every ounce of effort. It truly takes a village of people to make the journey possible and worthwhile.

But what are my takeaways?

Be friendly with error! One of the most valuable lessons I've learned is to embrace mistakes, not just in the classroom but with the learners and myself. This lesson, repeatedly stressed by my trainer, has been a guiding principle in my practice. Mistakes lead to the most significant learning.

Trust in the 3-year cycle! If I trust in the beauty of the Montessori 3-year cycle, there is time to absorb, synthesize, practice, and master.

Observation is key! Honing this skill takes practice, time, and thoughtful reflection. Observation led Montessori to design, redesign, change, adapt, and perfect each material and lesson. Observation is vital to knowing the child. Observation is a critical component of any Montessori classroom, and it takes effort to be consistent.

Hold tight to what I learned in training! What is Montessori pedagogy? Why did Dr. Montessori do things the way she did? She invested decades of her life in the observation of children. She transferred that observation into concrete materials and a learning method that guides children to become their authentic selves. I can trust in that science.

One of the most rewarding lessons I've learned is that the joy and enthusiasm I bring to the classroom mirrors the pleasure the children experience in their learning. I feel a deep sense of fulfillment and gratitude as I enter the classroom daily, realizing how fortunate I am to be in this role.

As the 40th school year of The Children’s House comes to a close, we prepare to participate in some of the time-tested, community-building, heart-warming traditions that make our school what it is to the children, the families, and those who work in this community of learners. These traditions and others throughout the year enrich all of our lives and create the culture that binds us together from the youngest child in Nido to the graduating 8th year. Sharing our traditions with those who are new to our community helps them obtain a deeper understanding of what matters to us and hopefully connects them to our community on a deeper level.

Traditions exist and are developed in each classroom to build community within these smaller groups of learners; however, the traditions that are practiced on a school-wide basis are the connecting fibers that link each classroom community to the whole which is The Children’s House and Compass Junior High.

The school year opens with the Fall Festival, in preparation for which elementary and junior high learners work with our amazing kitchen staff to welcome the entire school community to a day of celebration. We gather in the Barn and partake in a delicious meal made from the local harvest and then head outside to play games and participate in arts and crafts. Family members can volunteer to help set up, clean up, or support an activity. In starting our year together this way and celebrating the abundance of our harvest and the joy of being together, we begin the year knowing that we are all part of something bigger that aims to support our learners in the most loving, kind, and thoughtful way.

As the year progresses, the children participate in activities within their classrooms in ways that are meaningful for their developmental stage. Lower Elementary celebrates Pumpkin Fun Day (which falls on Halloween) but other classrooms recognize this time of year too, in ways that make sense for them. Elementary also celebrates the 100th Day of School, Primary has an annual pajama day, and Valentine’s Day is celebrated as well. (Classroom Highlights and Waypoints are great ways to know what’s coming your children’s way!)

Before we gather for our Harvest Feast in late November, our school plants daffodil bulbs on Daffodil Day in memory of Anna Maas, Sierra Fetterolf, and Rowan Sanford. Later that month, Elementary and Junior High students gather in the Barn for a meal inspired by the story Stone Soup, while all the other classrooms feast potluck-style. Less than a month later we gather as a whole school once again for the Seasonal Sing before we leave each other for winter break.

Celebrations abound at the end of the school year. They bring us together to sing on May Day, sing and share our community on Grandparents and Special Friends Day, and, finally, acknowledge the wonder and majesty of it all on our last day of school Dance of the Cosmos. This year we will establish a new tradition, Nadine’s Day, in honor of Nadine Elmgren and the years of love, inspiration, and commitment she brought to The Children’s House. You’ll find us outside on this day, playing, picnicking, and beautifying our campus: the place where all the people who make these traditions meaningful come to gather. See you again soon!

If you have spent any time with small children, you have likely experienced a not-so-pleasant mealtime. Perhaps your child refused to eat, threw food, or completely melted down at the table. Mealtimes can be stressful and overwhelming. While I don’t expect this blog post to eliminate power struggles at the table, I do think there are a few things to implement that can support your child’s relationship with food and improve your family’s experience around mealtimes.

For starters, less is more. Children are often overwhelmed by large portions of food. When plating your child's meal, start with just a few items. A single carrot, a small scoop of pasta, and a few berries can go a long way. With these smaller quantities, your child is more likely to finish a part or all of the meal and ask for more. Not only does this method help with overwhelm, but it also sets your child up for success.

Try to include something in each meal that you know your child likes. They don’t have to like all of the parts, but at least one item should be “safe” and appealing to them. They might start by eating this familiar food and then branch out to the other items on their plate.

Eat with your child; as with anything, children love to imitate the adults around them. If you are eating the same food, they are much more likely to give it a try. It is also important to eat at the same place as your child – whether you sit at a low table with child-sized seating, or bring your child up to an adult-sized table with a Tripp Trapp Chair or something similar.

Avoid attaching morality to food. Food serves many different purposes; a source of energy, comfort, celebration, and a reason to gather. While not all food supplies the same amount or kind of nutrition, all food has value. For this reason, avoid labeling things as “good” and “bad”. This does not mean that you should not provide a well-rounded diet for your child, but you should abstain from creating feelings of shame or guilt around food/eating. Remember, your child has a much stronger sense of intuition than you and me. As adults, we have been swayed by judgments and messages in our environment. It is our job to protect the pure, intrinsic drive of the child while providing them with a variety of flavors and experiences.

Involve your child in the before and after parts of mealtime. With proper child-sized and child-safe tools, they can help chop, stir, peel, etc. Your child can also help set the table, clear the table, and wash dishes. This involvement will help your child feel like a valued member of the family and will increase the likelihood of them being excited about the meal. Having a routine before and after eating also helps your child know what to expect, and young children thrive off of predictability.

Gathering around food is such a universal experience. So much beauty can come from these moments together: the start of a conversation, the shared enjoyment of a flavorful bite. These good feelings around food and eating start from the day your child is born – beginning with the eye contact and comfort they experience when being breast/bottle fed. Take the time to connect during these moments and enjoy the abundance that food can bring to you and your child.

A few months back, Alison Breithaupt wrote a blog post on The Evolution of Guiding, in which she shared her observations of children, throughout her career. At one point, Alison discussed the effects of technology on our children and how important it is for children to make sense of their worlds through real-life experiences and limiting access to screens. Does the mere mention of this cause you some anxiety, stress, and worry? Well, I am here to say I am right there with you! This blog post is an honest recount of our family’s journey through excessive screen time, a diagnosis of ADHD, and the shift to a screen-free childhood.

I will paint a quick picture. We, as adults, work all day, pick the kids up from school, and get home. We have a laundry list of things to do, dinner to make, e-mails to write, and all your child wants is your full, undivided attention. What is a little screen time? No worries! No more fighting. We can cook and answer emails without fighting. It is a win-win.

For our family, it was not the weekdays that felt so hard but rather the weekends. Saturday morning, my child would wake up, run downstairs, and sit in front of the television. Everything else went by the wayside. They were not interested in food, playing, outside, toys, helping out with tasks, etc. I could not pull them away from the screen! Every second of our time together became, “When can I watch a show?”

The lingering effects of my child watching any amount of television did not feel typical. They lost their ability to control their impulses. Emotional reactions began to not fit with the events that had taken place. In school, they shied away from anything that felt like it would take too long or could be too challenging. This did not feel like my child. It felt more like an addiction. We tried everything. We tried TV only on the weekends. I told myself I was doing great because my child did not watch any screens on weekdays. We tried only documentaries (educational, right?). We tried thirty minutes a day in the afternoons when downtime took place. Screen time was a constant fight and power struggle. None of the solutions we came up with produced a positive outcome.

Around this time last year, my 6-year-old was diagnosed with ADHD and Dyslexia. The more I read, the more I understood the intensity of this issue with screens. My child with a “race car brain and only bicycle brakes (a child psychologist’s explanation to my son about ADHD)” was merely self-medicating with screens. I still had no idea how I could possibly break this habit. However, upon our arrival here in Northern Michigan, we started to see a new pediatrician, who held our hands through our new diagnoses. One of the first questions she asked was about screen time. I clammed up, took a deep breath, teared up a bit, and was completely honest. Her advice: cut it out cold turkey! That is just what we did, and the results have been beautiful!

Please know it was not all sunshine and roses, nor is this meant to be a judgment on how others should parent. It was one of the hardest things we have done as a family. We now fill our time with the outdoors, board games, drawing, reading, coloring, painting, and much more. Without screen time, we all had to find other ways to fill our love of stories. The results: we all grew closer together and found new interests! Sometimes it is okay to be bored and not know how to spend your time. Incredible growth comes from that place. My child, who once shied away from a challenge, started to take on more and more. They still struggle with taking on challenges by themselves at times and we have been delighted in how often they take on these challenges more willingly. Their attention span grew. Their desire to be a contributing member of the family grew. Academic skills that once felt too hard or unattainable began to flourish with all the effort and hard work our child was pouring into themselves. It felt like we were seeing our child in a whole new light.

As for us, we are learning to put our phones and computers down more and be present. It feels lighter and more joyful. There are certainly harder days than others. We still have family movie nights about once a month, and it feels so different for us all to sit down together. We do not know if this is forever, but for now, we could not be happier with this drastic change!

Dr. Maria Montessori addressed the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1950. She stated, "It is the young people, the children, upon whom we may base our hopes of building a better world since they can give us more than we have today, and more than we, at one time had, but have since lost.”

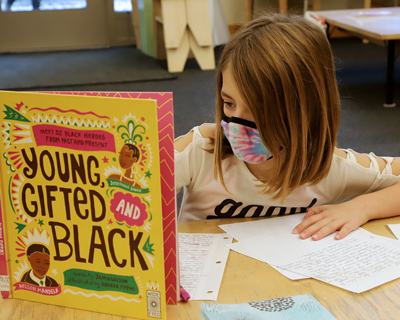

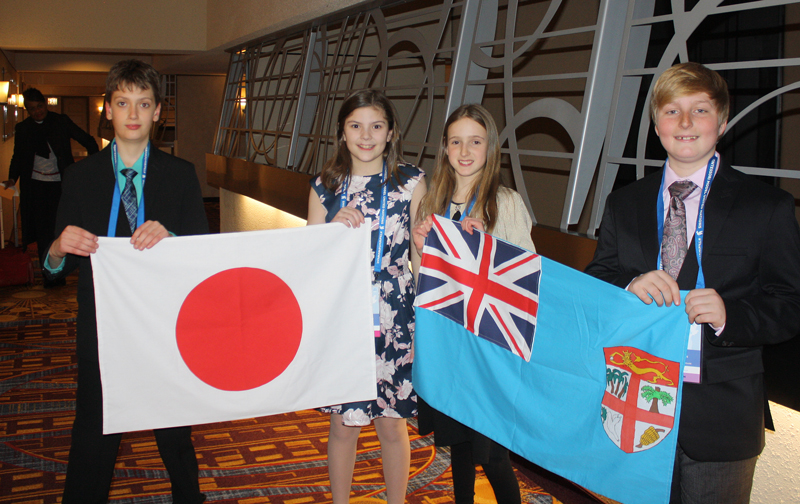

From the beginning, Montessori education has had a focus on world peace. At The Children's House peace education is woven into many daily activities. Even the youngest children in our school, the Nido infants, begin learning to be part of their community in a calm, peaceful environment. The Young Children’s Community (YCC) learners begin to explore the world together and contribute to their group by helping to clean, prepare snacks, and assist classmates- along with other responsibilities. Once in the Primary classroom, children begin to look at the world outside our campus through maps, books, and oral stories, while continuing to work on grace and courtesy skills. The Elementary learners begin to go out into our community, learning how to help by delivering meals and collecting food for local food banks, partaking in environmental clean-up days, and visiting the elderly- among other activities. All of this is the beginning framework for creating lasting peace.

During their final year of Elementary, sixth-year students have the opportunity to act as UN delegates in the Montessori Model United Nations program, where they collaborate with students from five continents! In September, they begin studying their selected country and they take that country's perspective in solving some of the world's biggest issues. This year, for example, our learners looked for solutions to issues such as the implementation of the United Nations convention to combat desertification, empowering youth in inclusive and sustainable food systems, and disaster risk reduction, among other topics. The learners spend many hours researching and writing position papers for their topic. Once they have laid out their country's position they write speeches to be delivered in their committee sessions, which are then shared with the Secretary General of the United Nations. This is huge work- the work of creating a pathway to world peace! There are no awards for the best position paper or highest quality speech, it is truly a collaborative experience. We are raising the leaders of tomorrow. I encourage you to learn more about how the Montessori Model United Nations helps students take part in our global community.

Power struggles between children and caregivers are a common part of a toddler’s development. Early on they develop a strong sense of order, which helps them make sense of their world. They observe how things are to be done and this becomes their perceived reality. However, this reality does not always align with the adult's reality and often a power struggle ensues.

How can we manage a toddler power struggle?

We must understand that what most toddlers want is power, control, and autonomy. We can offer them those things through opportunities to make choices. During a power struggle, the adult’s role is to help guide the toddler in a patient, firm, and loving manner. We must not join them in their fury. This is done by having clear, concise, and consistent expectations. Our job is to support their autonomy while simultaneously setting clear boundaries.

Below is an example of how to work through a power struggle:

A child is trying to cross the street without holding an adult’s hand.

The adult says, “I can’t let you cross the street without holding my hand, my job is to keep you safe. I see that this is upsetting you and I know you really want to do this by yourself. I will let go of your hand once we have reached the park.”

If the child refuses to walk while holding your hand, you could first offer a choice. Say to the child, “You choose- hold my hand or we don’t go to the park, which will it be?”

Maybe that logic will work and that’s great, or this might make things escalate, in which case you’ll have to decide what to do for them. You may need to pick them up and try again another day. The important thing is to stick firmly with the expectations you have laid out and the next time this situation arises, your child will know that if they do not hold your hand, there will be consequences (of their own choosing).

Power struggles often look like a moment of angst. The child may get mad or sad when something doesn’t go their way. They may show they are upset by lashing out physically; kicking, hitting, screaming, or pushing, and while they are allowed to have an array of big emotions, certain behaviors do not have to be accepted. The adult needs to stick with the established plan/limit, restate the expectations, and be patient with any recalibration the toddler needs.

As an adult it is hard to see children be upset, our hearts often want to fix everything for them. But, it is important to remember that children thrive inside clear guidelines, it makes their world feel safe. When a child feels safe they feel free and able to act independently.

Preparing food with children is my favorite activity in the classroom. Seeing their enthusiasm about making food, tasting it, and eating the finished product is very rewarding.

Why is teaching children about preparing food so important?

Involving children in preparing food not only shows them how things are made, but also develops many fine motor skills such as: spooning, scooping, dumping, precise pouring, tonging, ladling, cutting, spreading, scraping with a spatula, whisking, mashing, etc. Food by itself is motivating for a young child and the process of preparing it develops concentration, patience, persistence, and memory (due to many steps involved), in addition to comprehension of sequencing. Sharing food with others fosters a real sense of community. Lastly, children are often more willing to try something that they made by themselves.

When cooking with young children, it is important to remember a few things that will make the whole process easier:

- Plan ahead and know your recipe. Have all the ingredients ready and premeasured. Toddlers have short attention spans, and their skills are just developing. The ingredients should be lined up on the tray or table in the order in which they should be added to the mixing bowl. Organize them horizontally from left to right. Combine dry ingredients: flour, salt, and rising agents in one bowl, to limit the amount of containers/bowls.

- Children present different abilities, based on age and frequency of practice. The very young child (14 months) might be only able to dump/vigorously pour ingredients with our help. The older child (18 months) is capable of spooning and scooping. The older toddler is capable of performing the whole baking project independently.

- There will be misses and messes. Be patient and friendly with errors. Involve the child in the cleaning process.

When preparing food with children, it is important to provide tools that are child-sized and easy for them to use. Manipulating kitchen gadgets strengthens the hand muscles and satisfies gross motor needs, especially tools with cranks.

I would like to share a few of my favorite tools that we often use in the YCC when preparing meals with children:

Cutting tools: crinkle cutter or plastic knife. The children chop bananas, sticks of cheese, slices of apple/pear, melons, carrots, grapes, and strawberries. When the children develop the skill of rotating the wrist, they use the knife to cut.- Ceramic vegetable peeler: works well on carrots and cucumbers. Toddlers are very successful with using it!

- Grater with crank: my favorite thing about this grater is that it keeps a child focused and occupied for a long period of time. We use it for grating cheese, carrots, apples, and zucchini for muffins, or cucumbers for tzatziki sauce. For a toddler, it works better when food is chopped into smaller chunks. Because it takes a long time to grate, we usually prepare cheese or carrots a day before we need to use them in the recipe. Your child can grate the cheese for the next day’s meal, while you are busy cooking.

- Non-slip juicer or juicer with a crank. The second juicer works with melons, watermelons, grapes, and kiwis.

- Garlic chopper and silicone garlic skin remover: we often use it for preparing garlic for hummus, tzatziki, etc

- Grape cutter for toddlers makes round produce safe for toddlers to eat by cutting it into four pieces. It's a fun activity for toddlers and works with grapes, cherry tomatoes, strawberries and blueberries!

Video by Tree Sturman, Junior High Guide

Last week marks the third time we have traveled to Georgia and Alabama for our “Civil War to Civil Rights” Workshop. Each visit is a unique, one-time experience that is shaped by geography, location hours, restaurant hours, and special events in the area, not to mention the personalities and interests of twenty-three young people. Since our trips are not curated by a travel company, we are able to linger longer when there is interest, or add a stop if we stumble upon something interesting or unexpected. We are also able to experience local fare, as opposed to visiting large chain restaurants (don’t worry, we call first!!). So with all of this latitude, what did we do? Well, here it goes!

Monday

The vans rolled out at 7:30. Not to jinx us, but this crew has been very punctual this year! After an uneventful drive to Grand Rapids, we boarded a flight for Atlanta. The plane had “screens,” so it was a nice quiet ride. If you’ve flown into Atlanta, you know it was a half-day journey from our gate to our rental vehicles. We stopped off and did some Kroger-ing for breakfast and lunch supplies and then continued on to our rental abode for the week. After settling in, we got to work on roasting chicken for wraps, and baking breakfast casseroles. Each night, we sit in circle to reflect on our day, as well as prepare for the next.

Tuesday - Atlanta

We started our day with wonder. The Georgia Aquarium is one of the top aquariums in the nation. They have tanks large enough to house not one, but two Whale Sharks, along with a couple of Manta Rays; both beautiful, graceful, and so peaceful, gliding through the water, paying no mind to the onlookers. The Beluga Whales and penguins, on the other hand, wanted to check out our faces and inspect these creatures on the other side of the plexiglass. After a peaceful morning at the aquarium, we enjoyed our first packed lunch in the shared space between the aquarium, Coca-Cola, and the National Center for Civil and Human Rights. Of course, we had to drop into Coca-Cola to check out the swag, and share a Coke.

The National Center for Civil and Human Rights is a museum designed to guide visitors through the time of segregation and Jim Crow up through the present. Visitors can hear stories from Freedom Riders, participants in the Lunch Counter Sit-ins, interviews with government officials and police officers from the time period, and students who were the first to desegregate the schools. One part of the exhibit is an interactive lunch counter sit-in, where visitors can sit at the lunch counter with headphones on, close their eyes, and hear what those student activists may have heard when they sat at the “whites only” counters. The exhibit ends with human rights offenders and defenders throughout history and around the globe.

After an afternoon of some pretty heavy experiences, we bookended the day with Hamilton, at the beautiful Fox Theater in downtown Atlanta. Ironically, the calls for freedom from the founding fathers were echoed in the stories of civil and human rights that we had been listening to all afternoon.

Wednesday - Atlanta

We started our day at the Atlanta History Center, the home to the “Battle of Atlanta” Cyclorama. Cycloramas were the “virtual reality” or “IMAX theaters” of their time. The cyclorama gave the visitor the feeling of standing in the middle of a battle. Originally created by Europeans to be displayed in Minnesota, it depicted the victory of the Union over the Confederate forces. It has been altered throughout its existence for marketing purposes- at one point the blue of the Union was painted red to show a Confederate victory!

After a packed lunch, we headed to Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, to see the backdrop of the battle for ourselves. Two students helped set the scene when they volunteered to dress up as soldiers to help us learn about the similarities and differences between infantrymen of the Union, and those of the Confederacy. We ended our visit by getting a glimpse of what those soldiers saw as they ran into battle: a large open field to cross, and a mountain to climb.

Our next stop was Marietta National Cemetery. After the war ended, the federal government sought soldiers buried at field hospitals, on battlefields, and near railway stations. Marietta was one of the first places those bodies were reinterned. We learned that Marietta holds only Union soldiers, as at the time, the animosity was still so high that the locals did not want their dead buried with “Yankees.” We finished our night enjoying various cuisines in downtown Marietta at the Marietta Square Market.

Thursday - Birmingham

Road trip! Bright and early we headed for the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. We had seen this place from the outside on previous trips, but this was our first opportunity to visit. We started our tour by meeting a “Foot Soldier” of the Children’s Crusade. Miss Ann was 16 years old when she skipped school to join a march to talk to the mayor about segregation. “Bull” Connor, Birmingham’s commissioner of public safety at the time, sent the police force out with water cannons, hoses, and police dogs to end the march. He sent so many children to jail, they had to use school buses to transport them. The outcry from the nation who saw children being hosed and jailed led to the tipping point for President Lyndon B. Johnson, who soon signed the Civil Rights Act. Kelly Ingram Park, across the street from the museum, commemorates that day with sculptures of the events.

After our tour of BCRI, we met with Miss Dee, who works locally to bring resources into the community with the support of the Brookings Institute, which is investing in Birmingham specifically for its segregated communities and large African American population. She talked about how Birmingham is more segregated now than it was back then, because after the Civil Rights Act was signed into law, Whites left the city center. Staying downtown, we headed over to Yo Mama’s Fried Chicken for lunch, and honestly, the best fried chicken and waffles I’ve ever had.

After lunch, we visited the 16th Street Baptist Church. There, our docent, a former Michigander and graduate of Wayne State, shared the history of the church, as a place of community, and Civil Rights work. This is where the Children’s Crusade was organized, and where four little girls were killed when a bomb was planted outside under the steps. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. came to the 16th Street Baptist Church to deliver the eulogy for those little girls. They are memorialized in Kelly Ingram Park with a statue depicting a vision the lone survivor had of the souls of her sister and friends who were murdered that day.

Friday - Further south to Montgomery

Before leaving for our trip, we read the book “Just Mercy” by Bryan Stevenson. The book recounts his experience as a young lawyer working on death row in Alabama. The Legacy Museum and The National Memorial for Peace and Justice were started by Bryan Stevenson. He also founded EJI, the Equal Justice Initiative, a human rights organization in Montgomery. EJI, the museum, and the memorial are all paths for justice. The museum and the memorial work toward justice by providing the history and identification of those who lost their lives unjustly, either from enslavement, lynching, or unjust incarceration. EJI works to “end mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the U.S..”

We spent “recess” along the Alabama River at Riverwalk Park, passing a statue of Hank Williams (not Junior!), a famous Montgomery native, along the walk. To close out the day, we visited the old Greyhound Bus station, the site where a busload of Freedom Riders stepped off to be met by an angry mob that proceeded to attack and injure the Riders. The station now serves as a museum, exhibiting information about the Freedom Riders initiative. As we strolled the area, we saw the Alabama Capitol building, with the First White House of the Confederacy just across the street. The Capitol has two prominent monuments, one to those who fought for the Confederacy, and one to Jefferson Davis.

Our last stop before home was Pannie-George’s Kitchen for hot soul food - catfish, creamed corn, cornbread, and more.

Saturday - Last day, Atlanta

We enjoyed sleeping in and having a leisurely breakfast. We loaded the vehicles and headed for the National Center for Puppetry Arts. Four performers, in conjunction with the puppets, told the story of an eight-year-old girl, traveling from Chicago to Alabama to see her Grandma - a Black family traveling south in 1952. “Ruth and the Green Book” detailed the challenges Black folks faced as they traveled across the country, especially in the “Jim Crow” South.

Wow! In a cozy theater, we were dazzled by the combination of singing, dancing, staging, set design, and of course, a multitude of puppetry! Puppets included tabletop puppets, shadow puppets, and marionettes.

After lunch in a park, we continued to Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park. We toured the visitor center and attended a history talk at Ebenezer Baptist Church, the church where Dr. King grew up and where he eventually served as pastor, like his father and grandfather before him. The church lies just off of Auburn Avenue, also known as “Sweet Auburn,” which, before the Civil Rights movement, was the center for African American finance, entrepreneurialism, and culture. Our Park Ranger, Jake, told us the story of the King family as we sat in the pews, looking at the organ and the surrounding stained glass. The church was also the site of Dr. King’s funeral, where 200,000 people, including Robert F. Kennedy, waited outside to accompany the casket, being pulled in a cart by a team of mules, for a three-mile procession to Morehouse College. Being in the space and hearing the story was a profound moment for many in our group.

Contrast? We’ve got it! Our next stop took us to Stone Mountain, referred to as the “Mount Rushmore of the Confederacy.” Stone Mountain is a pluton, an upwelling of magma, or in other words a big hunk of granite, a REALLY big hunk. From a distance, it looks like a huge stone (800 feet high) sitting on the ground. Up close, you see a carving of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and “Stonewall” Jackson, riding horses and surrounded by a theme park. Under Georgia law, it is protected as a monument to the Confederacy. This proved to be the most surreal moment of the trip; we walked through a closed theme park, past a group practicing a performance for the Lunar New Year, up to the face of the mountain that is flanked by statues commemorating the “Valor” and “Sacrifice” of the Confederacy in their “fight for freedom, in the footsteps of the founding fathers.”

How do you begin to process the ever-changing landscape and history of one area? We went for dinner. Sweet Potato Cafe, just a stone’s throw from the mountain, welcomed us with fried green tomatoes, fried chicken, sweet potato fries, and black bean and sweet potato hash. The restaurant is locally owned, and farm-to-table. The owner, who is Black, asked us, “Why Stone Mountain?” It is always a challenging question to answer. The Confederate carving was not completed until 1972. It has been the location of KKK rallies. Its funding was provided by the Daughters of the Confederacy. The shortest answer? Because it’s still here. Georgia altered its state flag in 2001, but this monument and theme park are still here. Why does it still remain? With the ideals of the Confederacy still in the landscape, what does that mean for the people of Georgia? What does it mean for the U.S.?

In processing our trip, over the course of this week, our group shared a range of adjectives, adverbs, and abstract nouns to describe the experience which covered the entire range of emotions: courage, forgiveness, hopeful, sad, activist, humble, wondrous, reliable, inspirational, resilient, dangerous, rebellious, equality, terrorism, grief, hatred, fearless, determined, passionate, honorable, charismatic, sorrowful, faith, persistent, and peace - just to name a few. We discussed the similarities and connections we saw and also noted the contrast. We look forward to further exploration as the students begin their independent research and final projects.

“Where words fail, music speaks”

- Hans Christian Andersen

Where we have been -

This has been a year like no other. While I was preparing to begin my 4th year teaching at The Children’s House, there was some reflection upon what had come before- different projects, programs, focuses, etc. One thing I noticed was the impact that Covid had on the curriculum choices. These were not necessarily second tier choices, but projects that I may not have been drawn to if health concerns did not exist. As it was, the Primary got to learn about and try a new percussion instrument every week in group time. Lower Elementary embraced the ukulele and Orff instruments. The Upper Elementary built violins, and the Junior High created instruments out of found objects in the woods. The students’ creativity and ability to make music and art, in the face of adversity, is something I am grateful for.

Where we are -

This brings us to what we are doing now, this year. We have studied and learned how to play several different instruments these last few years, but there was one thing that was left out, a focus on singing. Partially for the obvious reasons stated above (I am avoiding saying the dreaded C---- word again). But, because singing as a group can be a tricky thing. Not everyone is comfortable being so vulnerable and open, to what can feel like, a critical ear. Our school community needed to be able to embrace the sounds we could make together before we could think about growing them.

The students seemed “game for it” this year as we started to focus on learning to sing better on pitch by using tuned bells and the piano to train their ears. Through singing short, new songs and introducing Kodaly solfege the students have developed a strong sense of high and low pitches and matching their voice to a pitch played. One of the best comments I heard while preparing for the Seasonal Sing was, “This part is too high for me.” That was music to my ears because that demonstrated a clear understanding of their vocal range and ability, identifying the issue, and then feeling comfortable enough to voice it to me as their teacher. While it may sound strange, I was extremely proud at that moment- that student had just shown me how much they had grown as a young musician and that we can work together toward a solution! The sense of pride and accomplishment the students had after the Seasonal Sing was one of the best moments to be a part of.

What’s next –

So, what do we go to next? Do we follow the model of constantly striving for something bigger and better? Do we go back to basics and focus on strong foundational skills? Ask the students what they want to do?

I am inclined to a mixture of those three. Give the students an option to work on all three ideas, allowing them to have a sense of ownership over what they are focusing their time on. The idea of working on larger long-term projects gives everyone a goal to work towards and working on fundamentals is incredibly important too. Furthermore, having a performance or showcase at the end of the hard work provides closure, or satisfaction, of a job well done. Thus, allowing one’s music to “speak for them”.

In June 2022, The Children’s House became an accredited member of the Independent Schools Association of the Central States (ISACS). Obtaining membership was a lengthy process in which every staff person and many other members of the community participated. Membership in ISACS is not a once-and-done process but enters the school into a continual cycle of accreditation and improvement. There are many reasons why being an accredited member of ISACS is valuable to the school community.

Who is ISACS?

ISACS is a non-profit organization that serves more than 240 member schools in thirteen states. The mission of ISACS is to lead schools to pursue exemplary independent education. Its vision is that ISACS schools empower all students to contribute and thrive in a diverse and changing world. Its core values are equity, integrity, and continuous improvement.

Why is accreditation important?

ISACS accreditation allows The Children’s House to reflect, learn, and grow as a community. It forces the school community to set aside time dedicated towards improvement based on what the school has been doing well, and opportunities that arise. It gives the staff a process to paint others a picture of what TCH strives to accomplish as a school community.

Accreditation is a group effort. To complete the process, it takes participation by the entire staff, and the wider school community including board members, parents, alumni, and donors. This is the one time in the community when everyone comes together to identify the school's strengths, acknowledge its challenges, and establish the priorities for school improvement moving forward. This collaborative process focuses on the entire institution, not the individuals within it.

Accreditation holds The Children’s House accountable for giving families the education that is promised when they tour and enroll. The self-study is a 100+ page report written every seven years and documents the school’s purpose and goals, its strengths, challenges, and plans for the future. The self-study is made up of many small reports, each examining different aspects of the school such as governance, curriculum, the community, administration, etc. The self-study is followed up by a visit of peer educators from other ISACS schools. This peer-review committee evaluates whether TCH is carrying out its mission and vision for educating. It allows others to take a deep dive within the organization, and make recommendations for school improvement based on observations and the self-assessment. The peer-review committee makes sure that TCH adheres to the ISACS Standards of Membership, which are elements that should be common to all independent schools. Opening up the school to this rigorous and continual review process gives it credibility and assures its integrity.

Seven-Year Cycle of Accreditation

Every year, the school is in a different stage of the 7-year accreditation cycle. Year one is preparation for the accreditation, which includes a school-wide survey. This is followed by the self-study process in year two. The following year is the year of accreditation when the self-study is published and an accreditation team visits the school. Year four gives the school time to write a reaction report to the ISACS Accreditation Review Committee and make plans for improvement. Years five and six are used to implement any changes and track the school’s progress. Year seven offers a year of review and reflection on what has been done in anticipation of the next accreditation cycle. The Children’s House is currently in Year 5 of its accreditation cycle.

Being an ISACS member school makes a statement that TCH is a school that takes learning and growth seriously. It gives the school community a larger independent school group that values this as well. TCH faculty have the opportunity to observe and review other schools. They can learn best practices from a larger network of educators. ISACS offers great learning opportunities for parents, administrators, and board members. The accreditation process makes the entire community lifelong learners, working together towards improvement. It is just one of the ways that The Children’s House works to fulfill its mission to the best of its ability, to prepare a Montessori environment that supports and respects the development of each unique child and nurtures them to become independent, curious, confident, lifelong learners who strive to contribute to their communities and the greater world.

Traditionally, school quality is judged by class size. Many believe a lower teacher-student ratio means more individualized attention and larger class sizes are thought to be a sign of less instructional time. This perception is founded on the idea that children learn more when they are one-on-one with an adult. Traditional schools view teachers as knowledge transmitters and children as empty vessels waiting to be filled. Montessori schools turn this accepted theory on its head. You won't hear us promoting small class sizes at The Children's House because we know larger communities with specific principles in place promote a different kind of individualized learning - one that educates children for life. Primary and elementary classrooms have around 25 children, so how do we do this and make sure each child's interests and needs are being met?

1. We have mixed-age classrooms.